|

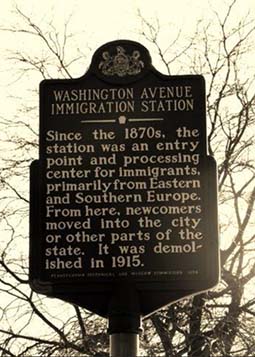

Pier 53 in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century. The Philadelphia immigration station at the end of Washington Avenue on the Delaware River (now known as the Washington Avenue Pier) existed from 1870 until it was torn down in 1915. Here are excerpts from Fredric Miller's Philadelphia: Immigrant City.

In 1873 the establishment of two modern steamship companies ushered in a fifty-year period of active immigration, during which just over a million immigrants arrived in the city and Philadelphia resumed its place as the fourth largest immigrant port in the country.

It transported most of the roughly 20,000 immigrants arriving in Philadelphia each year between 1880 and 1910. After World War I the line briefly resumed immigrant service from Liverpool, but when the United States severely curtailed immigration in 1924, the service came to a halt. |

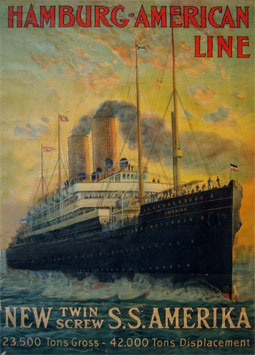

The station became one of the most colorful places in Philadelphia. Inside was a part of the examination room called the 'Altar'. Since under some conditions single women were prevented from landing, many hurried unions were celebrated on the spot. In 1898 the major German company, the Hamburg-American Line, started a run between Hamburg and Philadelphia which drew directly on the great Jewish and Polish migrations. Between 1910 and 1914, at the height of immigration from southern and eastern Europe, Philadelphia was the third most important immigrant port in the country. The fifty years of large scale immigration naturally had a profound effect on the city's immigration facilities. Philadelphia required almost all ships from abroad between the spring and the fall to stop first for a health inspection at the Lazaretto in Essington, eight miles downriver from the city. Vessels carrying passengers with infectious diseases could be isolated for up to several months at a complex that included a hospital capable of housing 500 patients. In 1919 the state ended its inspection service. In any case, Philadelphia had been more than adequately protected against imported diseases and after 1865 experience no epidemics of the cholera present in many European ports.

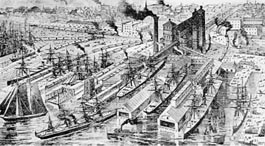

The fifty years of large scale immigration naturally had a profound effect on Almost all immigrants made their first contact with America at the piers and immigrant stations...for most who came through Philadelphia this was their only contact with the city, for relatives or employers took them elsewhere. From the 1870's through the early 1920's the area around the Washington Avenue wharves where the American and Red Star Lines docked...was an area of warehouses, factories, sugar refineries, freight depots, and grain elevators, all connected to the vast yards of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

|

Outside there was usually a crowd of entrepreneurs eager to charge the newcomers exorbitant rates for a variety of needed and unneeded services. The railroad owned the wharves, and because it effectively controlled the immigrant traffic, in the 1870s it had constructed a two-story facility for receiving immigrants. Having already had their medical examinations downriver, at Washington Avenue the immigrants passed through customs inspections and then went downstairs to a ticket office and reception area from where they could board trains and leave the city. About the Author: Frederic Miller was at the National Endowment for the Humanities. He held a Ph.D. (1972) and MLS (1973) degrees from the University of Wisconsin and was co-founder and co-director of the Public History Program at Temple University in Philadelphia. He co-authored Still Philadelphia: A Photographic History, 1890-1920, and had written several articles about British and Philadelphia social history, archival theory, and management. Ongoing at Washington Avenue Green is the Pier 53 Project—a historical study of the immigrants who arrived at the Pier from 1876 to the 1920's, their stories, and the stories of their descendants. Each story is part of a mosaic that contributes to the history of Philadelphia and its waterfront, and ultimately to the history of immigration in the United States. Here's the link to the Pier 53 Project page on this site. Pier 53 Project And here's the link to a recent podcast first aired on WHYY on June 14, 2018. It includes an interview with Susan McAninley and a description of Pier 53. Project.https://whyy.org/segments/a-quest-to-conjure-philadelphias-immigrant-past-at-pier-53/

|